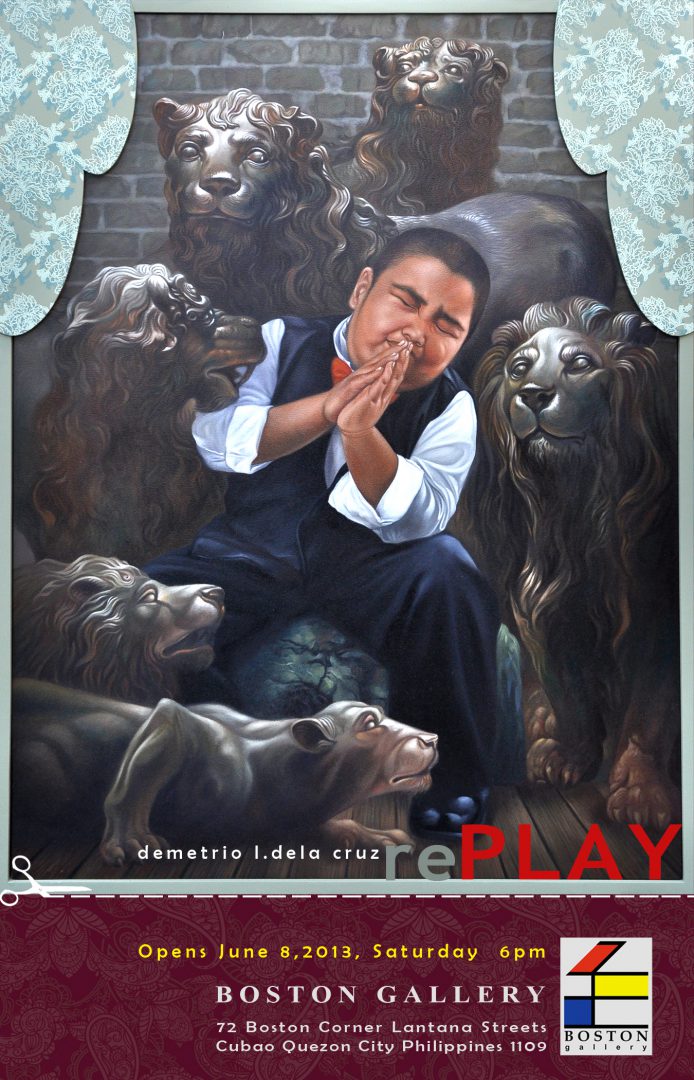

THE CHILDREN’S HOUR

By Alice G. Guillermo

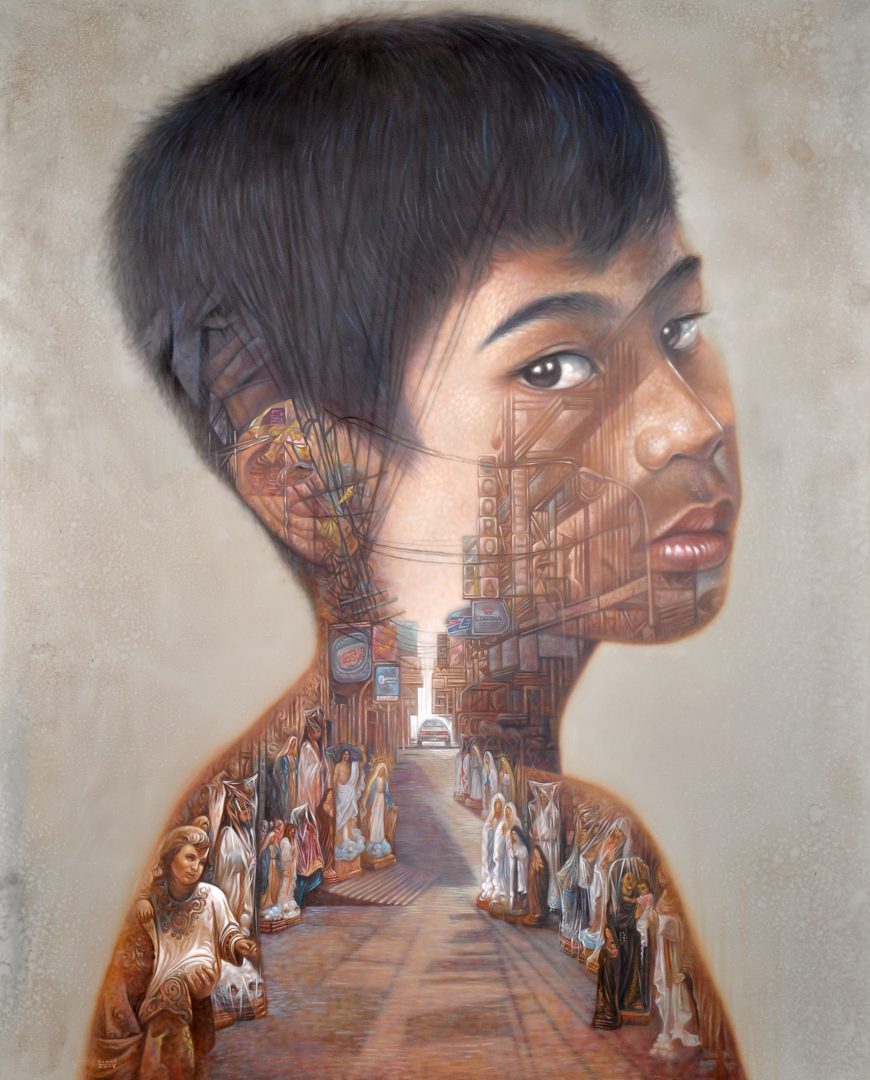

As in his previous shows, top realist painter and father of three, Demetrio de la Cruz, has been caught up with the theme of raising children in a healthy environment. His prime interest has been the close symbiotic relationship of children and the natural and social setting, nurturing and respecting nature without exploitative use and oppression so as to attain the elusive dream of a Peaceable Kingdom shared by humans and animals and all living creatures of the earth. His five paintings also constitute a life narrative that narrates the struggles of man in the course of his existence.

This time, the artist shows his concern for the growth of the child’s mind and creative imagination through storytelling and playacting. In pursuit of this delightful project, he draws widely from the world’s myths and legends and presents them in a stage setting. The artist himself explains the overlapping meanings of the title “rePLAY”: “Its about ‘play’ (kidstuff) ‘play’ (stage play) or ‘replay’ (regarding a play, and the form of being played again). It features kids mimicking, doing some sort of revival of scenes from classical paintings, as from the paintings of Botticelli, Rubens, etc. executed on iconic pop scale. From this very colorful and playful works, a subliminal message lurks: we are living in a digital world but also in the age of remix, recycle, retro, revival…is it that we come on the brink of running out on new ideas, that we have resorted to doing recycled things from music and the arts.”

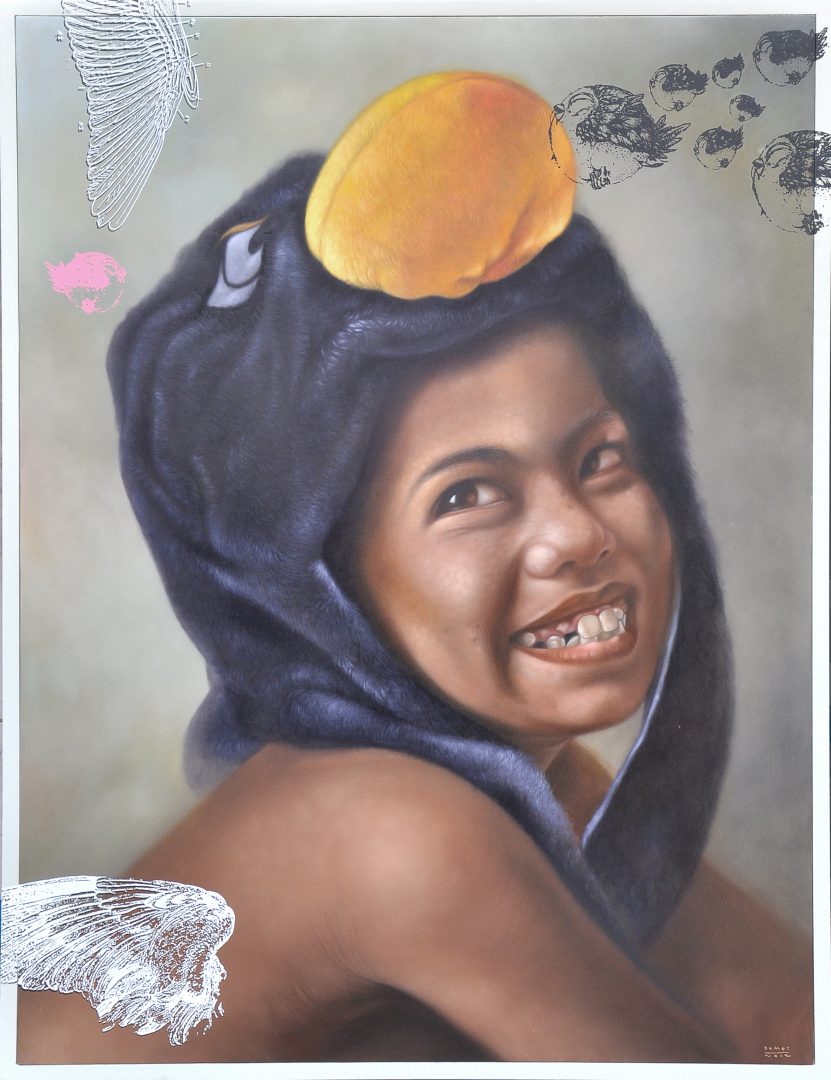

The first character in this world of replay is the narrator who opens the show. He is a lively and smiling pupil of the grade school who calls the viewers to attention and whose identity is supported by his two toys, one a real rooster flashing red and blue feathers, of proud mien, and the other an intricately-crafted sari-manok who seems to challenge his living counterpart—all of the three in bright, cheerful colors and standing on the wooden floor. They constitute the living world. But there is another dimension: from within the space of the finely-crafted wood curtains, a young guardian angel emerges. A classical figure, she is delicately molded in varying tones of gray, with subtle reflections on the face, torso, and strong wings and moving slightly forward as though to protect the little boy. A figure of the imagination, she represents the spiritual side of man. And it is the device of the wooden lace curtains that unifies them together in the space of art.

The second painting or scene in the play is a pop replay of Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus.” Like the original figure, the young girl also rises from the sea, but instead of the classical gravitas of the original, she wears an up-to-the-minute teen costume complete with pink heels as she rises from the big tridachna shell surrounded by sea creatures, among them whirling whales and smiling penguins.

Scene 2 entitled “Faith” centers around the character of a young robust boy in intense attitudes of prayer, a veritable Daniel in the lions’ den, as in the Biblical narrative. He prays for protection against the gray lions of temptation who surround and besiege him. But his prayers seem to have taken effect because the lions are now subdued and gaze at him dumbly without any obvious dangerous intent.

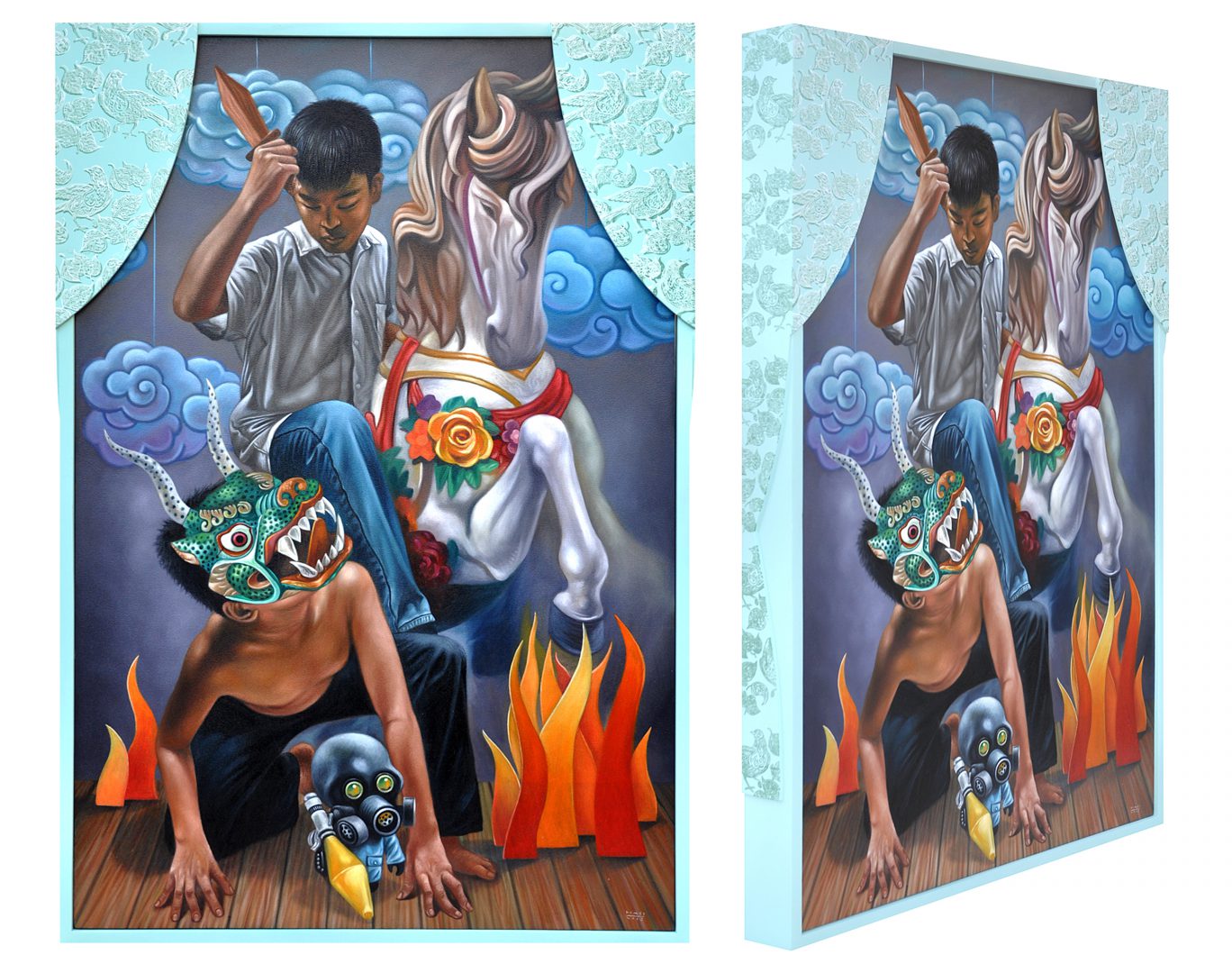

One of the most exciting works in the show is Scene 3 entitled “The Hunt” which seems to pit two scenes together, belonging to two different times, places, and cultures. In his style of modulated grays from the 19th century orientalist baroque with its frenzied scenes of the Crusades and the conquest of Constantinople, the movements of the Moorish warriors among their rearing steeds and rampant lions viciously gnawing flesh, as in the grim scenes from Delacroix’ Battle of Sardanapalus, Demetrio dela Cruz opposes to this a scene of the brightly-colored schoolchildren enacting the play by riding their plump plastic toys or stuffed animals of lions and bears with wanton ill-concealed delight. The narrative ends with Scene 4, “Victory”, in which a boy subdues with a small wooden sword the enemies who are now mythological beasts bearing fantastic horned masks or horses caparisoned in bright floral designs, accompanied by a small weapon-wielding robot. The mythical nature of the scene is enhanced by the clouds, like travelling whorls navigating the sky.

The painting style of Demetrio de la Cruz who worked for some time in graphic design and learned considerably from it shows an excellent committed realist painter surpassed only by a few of his peers. In this exhibit, the artist shows an excellent grasp of narrative as story or stage play. But what makes his work particularly unique is that it does not follow a unilinear one-dimensional trajectory which is customary in narratives. Instead, his story is multilinear and many-dimensional so that the narrative is split into several intersecting sections, including the temporal, spatial, and cultural. This certainly differs from the usual approach which is one-dimensional, for the artist is well aware of the richly overlapping dimensions of history, the intertextuality of the various human issues, as well as the inexorable element of change affecting time, space, and culture brought about by great global migrations of peoples in our world.

Indeed, one cannot help perceiving the gap in time, space, and culture that these narratives convey. And yet, the irony of it is that there is a bedrock that remains unchanged. Despite the grayness and gravitas of classical imagery as against the light, bright-colored present, of children with nary a care in the world, unaware of immediate realities, many of the bitter age-old conflicts and prejudices remain and the dream of the Peaceable Kingdom is still out of reach.

BOSTON Gallery

08 - 22 June 2013

Address:

72-A Boston Street Cubao

Quezon City

Metro Manila

Philippines